The British election has decided in favor of no one in particular. The possibilities seem confined to a Conservative minority Government or a Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition one. With so much going wrong for Britain (just look at the accidental disenfranchisement), the last priority of whatever the new British Government is will be their friend across the pond.

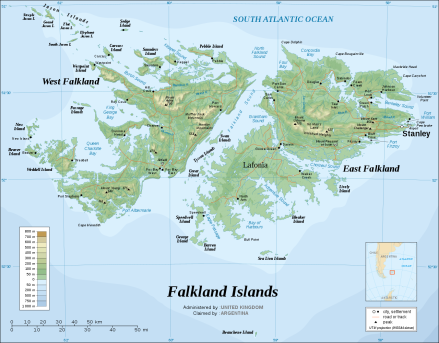

At the same time, Rockhopper has claimed to have discovered oil in the area of the Falkland Islands, reversing the disappointment felt by Desire Petroleum earlier this year. With these two events in mind, it seems like a perfect moment to look back at the last time the special relationship really came to the fore, while the Falklands were in the news.

One of the last vestiges of British empire, the likelihood that the Falkland Islands would ever become a household name – let alone the site of a major twentieth century conflict – seemed slim at best. Yet when the military government of Argentina dared to invade in April of 1982, the successful British retaking of the Falklands entered into the realm of legend and revitalized both Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government and Great Britain as a whole.

The extent to which American assistance was a crucial part of the British war effort is still debated. Paul Sharp claims that “Britain’s success in the Falklands War…would not have been possible without US support.”[1]Then-Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger downplayed the role of American aid, characterizing himself as a mere “assistant supply sergeant, or an assistant quartermaster.” He placed the glory of victory solely with the British:

Some said later that the British could not have succeeded if we had not helped. This is not so – I think the decisive factor was Mrs. Thatcher’s firm and immediate decision to retake the Islands, despite the impressive military and other advice to the effect that such an action could not succeed.[2]

While the revival of the wartime Anglo-American ‘special relationship’ did not necessarily ensure a British victory, the effects that American support had on British and Argentinian morale and indeed, world opinion, were significant. As Sharp explains, “had the Americans decided to oppose Britain’s recovery of the Islands, then the war would have been impossible and Thatcher’s political demise all but assured.”[3]

The sophisticated weaponry supplied by the Pentagon, such as the Sidewinder air-to-air missile and the Stinger man-portable surface-to-air missile, helped to minimize British casualties. Especially crucial was US intelligence. That support was all the more surprising as it constituted a near-complete reversal of the centuries-old Monroe Doctrine demarcating the western hemisphere as an entirely American preserve.

Declared at the height of Bolivarian revolutions sweeping Latin America and portending a sundering of ties with Spain, the Monroe Doctrine was pronounced at President James Monroe’s seventh State of the Union Address in 1823. The time having “been judged proper,” Monroe asserted that:

As a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved, that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers … We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those [European] powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety.

The independence movements seemed likely to draw the ire and full military might of Spain (or other predatory European colonizers seeking to capitalize on Spanish misfortune) upon the Americas. While the United States was incapable of backing up the doctrine with force, the very declaration served Europe notice that the United States considered the entirety of the hemisphere its exclusive domain.

For almost a century, it remained that way. There were instances of European Great Power meddling during the Civil War, but they were limited at best. Until the Spanish-American War, the United States was left to its own devices in the hemisphere, despite the lack of any military force to back up the Monroe Doctrine for the better part of the nineteenth century. Instead, America dealt mostly with the native political movements in Latin America, attempting to secure at least anti-Communist, if not pro-Washington governments. The Cuban Revolution was the clearest indication that American strategies might not be working, but fortunately Fidel Castro’s rise to power did not presage a ‘domino effect’ in Central and South America.

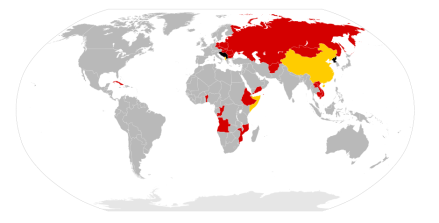

By the early 1980s, American anti-communist efforts in Latin America appeared to be faltering. The Vietnam War had ended in undignified withdrawal less than a decade before, and communism appeared to be on the move in Iran, Angola, Afghanistan, Grenada, and a host of other places around the world. Particularly troubling were the Sandinista movement in Nicaragua and ironically, the various Bolivarian movements throughout South America. Thus the Falklands crisis arose at a time when the United States was attempting to strike a precarious balance between its dedication to the west and its fear of a creeping communism.

Communist countries of the world in 1980. USSR-aligned countries in red, China-aligned in yellow, and independent communism in black.

David Dimbleby and David Reynolds call it “an impossible situation,” with President Ronald Reagan forced to choose between America’s closest ally and its best friend in South America.[4] While perceived by the British public as a general reluctance to back the United Kingdom, the hesitation on Washington’s part was warranted. Even attempts at mediation were discouraging to Whitehall, with Secretary of State Alexander Haig’s 33,000-mile ‘shuttle diplomacy’ seen as a disinclination to aid Britain at all.

Argentina had been a relatively reliable anti-communist partner, despite the distasteful ruling military junta led by General Leopoldo Galtieri. But continued intransigence from Buenos Aires eventually made up Washington’s mind for it. UN Security Council Resolution 502 was ignored, and despite several offers of mediation from both the US and Peru – the latter’s was even accepted by the British – Argentina pushed ahead with their invasion.

A potential complication for US support was the position of the Organization of American States (OAS), the regional framework for North and South America conflict resolution, which condemned the “the unjustified and disproportionate armed attack perpetrated by the United Kingdom” and called upon all member-states to aid Argentina. John Norton Moore condemns the OAS behavior before and after the war, accusing the organization of having “lost its principles.”[5]

Rather than a breaking of fellowship with the other nations of the Americas, the United States’ eventual support for Britain was all the more surprising because it was backing an external power in its own backyard. The U.S. was all too willing on numerous occasions to override prevailing OAS sentiment in pursuit of its own interests; that was to be expected. It was merely a continuation of the Monroe Doctrine. But by aligning with a foreign power, specifically Britain – largely the original target of the doctrine – America was overriding centuries of precedent and repudiating one of the foundations of its foreign policy.

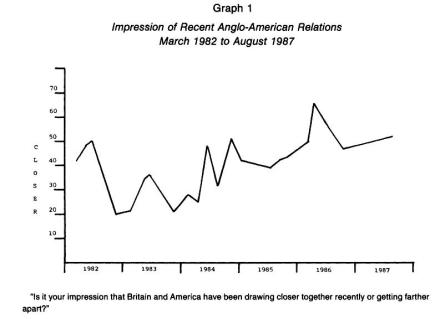

British attitudes towards the United States, 1982-87. From Jorgen Rasmussen and James M. McCormick, “British Mass Perceptions of the Anglo-American Special Relationship,” Political Science Quarterly 108.3 (Autumn 1993), 525.

Despite the existence of the ‘special relationship’ and the close ties between the British and American intelligence and defense establishments, popular sentiment towards the relationship had been on the wane in Britain since the 1960s. British popular opinion trended towards the two countries growing farther from each other. Even the eventual American support in the Falklands provided a temporary boost, with the sense of the two countries growing returning to its prewar level by late 1982. [6] The common refrain that Reagan’s United States was the greatest threat to world peace – as well as his bellicose posturing regarding nuclear weapons – had served to alienate many Britons. That in and of itself does not make the eventual Anglo-American wartime partnership surprising, but it does point to the increasing possibility of a special relationship sundered. Even after the relationship hit lows at the end of 1982 and ’83, British esteem for America only increased throughout the later 1980s.

Between the initial Argentine invasion on 2 April and the eventual American ‘tilt’ towards the British, 28 days elapsed. Much of that time was spent engaged in diplomatic negotiations with the OAS. Reagan’s cabinet was deeply split over the issue. Weinberger and his deputy, Lawrence Eagleburger, were devoted Anglophiles and all for an immediate commitment to support Britain. Jeanne Kirkpatrick, US Ambassador to the UN, was vehemently opposed. She referred to the Weinberger faction as “Brits in American clothes” and asked “Why not disband the State Department and have the British Foreign Office make our policy?”[7] Weinberger and Haig, maneuvering behind the scenes, convinced Reagan that if mediation should fail the United States would immediately and entirely throw its weight behind the United Kingdom.[8]

Despite the public show of neutrality and indecision though, the traditional intelligence and defense links between Britain and America had not been severed. The standard American posture towards Britain was not altered; continuity meant the same thing as neutrality. Said John Lehman, then-Secretary of the Navy, “there was no need to establish a new relationship … It was really just turning up the volume…almost a case of being told not to stop rather than crossing a threshold to start.”[9] From 5 April, shipments to Britain had in fact been increased under the watch of Dov Zakheim, one of Weinberger’s appointees, and military aid to Argentina had already been mostly suspended, owing to the military junta’s abysmal human rights record.[10] All that remained was for existing arrangements to be made official.

Only a day after the invasion, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 502, demanding an immediate ceasefire and Argentine withdrawal.[11] Again, the Argentinians held their ground and continued to forge ahead with the invasion. Further American and Peruvian efforts to mediate a settlement were again ignored. Reagan had little choice but to follow Haig and Weinberger’s advice and side with the British in the face of such dedicated Argentine intransigence. It was not a foregone conclusion, as Duncan Anderson calls it: “there was not the slightest prospect of the United States supporting Argentina against Great Britain.”[12] While absolutely true, neutrality was a viable alternative for a time. Washington finally leapt in when there was no other alternative.

The OAS was quick to denounce the United States’ support for Britain. A spokesman for the Venezuelan embassy accused the U.S. of “siding not with its little brother but with its stepmother.” One Brazilian commenter claimed that it was now clear America had first- and second-class allies. Only the former British colonies in the Caribbean took Washington’s side.[13] But the die was cast, and the United States moved quickly to make good on its promises.

After a month of American indecision, the suddenness and decisiveness with which American aid was thrust upon the British was close to miraculous. The United States provided everything except for manpower. The American base at Ascension Island (ironically, leased from the British) was now the closest one to the combat zone, albeit still 3,800 miles away. Weinberger took steps to cut through the “infamous” Pentagon bureaucracy and deliver materiel to the British as quickly as possible, reducing the usual procurement time of six weeks to about twenty-four hours, with some even arriving within six hours of the initial request. He gives an account of the weapons and equipment being delivered:

The first requests were for missiles, particularly our Sidewinders, the AIM 9-L air-to-air missiles, with which the British wreaked such havoc on the Argentines, and aircraft fuel. But initially we had to, and did, add enormously to the facilities at Ascension to receive and deliver the fuel and other supplies to the British task forces’ ships and planes (we also sold them twelve of our F-4 fighter planes at a “bargain basement” price after the war, in order to allow the British to keep a Phantom squadron on the Falklands).[14]

By 1982, the F-4 was hardly a frontline, state-of-the-art fighter, but it was still a valuable piece of technology that the United States was ready and willing to share with Britain. The Sidewinders certainly were state-of-the-art; as one of the first all-aspect air-to-air missiles in the world, it allowed RAF pilots to shoot down Argentine planes from any angle in the sky. Between 1 May and 23 June, 27 Sidewinders were launched. 24 hit their targets.[15] No longer were the British confined to trailing behind enemy fighters.

As for the overall strategic picture, Anderson invokes the grim specter of a South Atlantic winter. “Without American logistic support, most of which was channeled through Ascension Island, the operation would have taken much longer, and would undoubtedly have been compromised by the onset of the southern winter.” Getting to Ascension in the first place would have been impossible without the 12.5 million gallons of aviation fuel provided by the Pentagon.[16] Between the logistic, aviation, and intelligence requirements of British forces, the case is clearly weighted towards a decisive American contribution. It was significant in the sense that without the support, the British effort would have taken far longer, suffered many more casualties, and possibly affected Prime Minister Thatcher’s government in the UK general election.

Towards the end of the war, by the 21 May landings, it was increasingly clear that the British had the upper hand and were going to emerge victorious. The primary concern in Washington became setting the proper tone for the postbellum situation. In the words of Dumbrell, Haig shifted his emphasis to “avoiding an Argentinian humiliation and towards pressing on London the virtues of magnanimity.”[17] At stake was the very legitimacy of the Galtieri regime and the Argentinian state. However, for Thatcher, negotiation over the Islands was a nonstarter. As Americans cheered in the White House Situation Room when the end to hostilities was announced, London embarked on an expensive garrisoning of the Falklands, and refused any initiatives to discuss their status. Meanwhile, Britain’s sense of national pride and confidence had been restored over the course of several months.[18]

Almost immediately the carefully cultivated special relationship returned to its pre-Falklands bickering. The standing of Margaret Thatcher was affirmed in American popular opinion: the ‘Iron Lady’ was now a fixture on the world stage and a major player in the coalition of the west. Her reelection in 1983 came easily, the war having solidified the Tories’ position. British opinion of America did get a boost from the latter’s support, but it was short-lived, shrinking back to prewar levels by winter 1982 and evaporating after the 1983 American invasion of Grenada.[19] American support for Britain somewhat soured in return after Thatcher refused to back the Grenada expedition, seen as avoiding the responsibility of ‘paying back Washington’ for its support in the Falklands.

Perhaps that reluctance – or even denial of the need – to ‘repay’ America for siding with Britain came from the official London downplaying of the American role. John Nott, the British Defence Secretary, thought that America was “almost indecently keen to save Galtieri’s face, with only France giving unqualified assistance.”[20] American officials like Weinberger were equally likely to diminish their own part in the war.

While Margaret Thatcher continued to insist on Britain’s devotion to the United States, rifts in her own cabinet and in the lower echelons of both Washington and Whitehall seemed to drive the two countries apart. When she stood with America, she often alienated herself from the rest of her government, and vice versa. In that sense Thatcher herself was one of the defining characteristics of the special relationship in the 1980s.

Margaret Thatcher’s address to the Conservative Party in October 1982.

But regardless of the consequences – or rather, because of them – the American tilt towards supporting Great Britain in the Falklands War came as a shock to Britain, the OAS, and indeed most of the world. The materiel, bases, and intelligence provided were invaluable in bringing the war to a swift end without an excess of casualties. The American position in the Falklands was most certainly significant, and to a large extent surprising. But perhaps the most startling aspect of this is that the support should have come as a surprise to anyone. It was just the newest incarnation of the 200 year-old special relationship.

[1] Paul Sharp, Thatcher’s Diplomacy: The Revival of British Foreign Policy (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998), 101.

[2] Caspar W. Weinberger, Fighting for Peace: 7 Critical Years in the Pentagon (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 1991), 215.

[3] Sharp, Thatcher’s Diplomacy, 101.

[4] David Dimbleby and David Reynolds, An Ocean Apart: The Relationship between Britain and America in the Twentieth Century (London: BBC Books, 1988), 313-314.

[5] John Norton Moore, “The Inter-American System Snarls in the Falklands War,” The American Journal of International Law 76.4 (October 1982), 830-31.

[6] Jorgen Rasmussen and James M. McCormick, “British Mass Perceptions of the Anglo-American Special Relationship,” Political Science Quarterly 108.3 (Autumn 1993), 525-26.

[7] Dimbleby and Reynolds, An Ocean Apart, 314.

[8] John Dumbrell, A Special Relationship: Anglo-American Relations from the Cold War to Iraq (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 197-98.

[9] Quoted in Dimbleby and Reynolds, An Ocean Apart, 314-15.

[10] Dumbrell, A Special Relationship, 198.

[11] Domingo E. Acevedo, “The U.S. Measures against Argentina Resulting from the Malvinas Conflict,” The American Journal of International Law 78.2 (April 1984), 323-24.

[12] Duncan Anderson, The Falklands War 1982 (Oxford: Osprey, 2002), 24.

[13] Dumbrell, A Special Relationship, 202.

[14] Weinberger, Fighting for Peace, 213-14.

[15] Christopher Chant, Air War in the Falklands, 1982 (Oxford: Osprey, 2001), 79.

[16] Anderson, The Falklands War, 24, 26.

[17] Dumbrell, A Special Relationship, 199.

[18] Dimbleby and Reynolds, An Ocean Apart, 315-16.

[19] Rasmussen and McCormick, “British Mass Perceptions of the Anglo-American Special Relationship,” 525.

[20] Dumbrell, A Special Relationship, 200.

Pingback: Military History Carnival #25 « The Edge of the American West

LAS MALVINAS SON Y SERAN ARGENTINAS. PIRATAS HIJOS DE PUTA

More whining and bitching from the devious and deceitful Argentinians…can’t and should not be trusted.

Ellos nunca fueron suyos, para empezar.

Pingback: US promised India help if China attacked during 1971 Indo-Pak war

Since the people of the Falklands want to be British, they should remain British.

Like most wars, this one should never have been fought. People decide to whom they have loyalty. The people on the islands think they are part of the UK; They have been for hundreds of years. They viewed the war as a violent invasion by Argentina. Almost 1,000 people were killed for nothing. Millions were wasted. Why? To conquer a wind swept land, sparely populated, whose main industry is sheep raisiing.

Argentina has legitimate interests. The UK has legitimate interests. This should have been settled without combat.

” … But by aligning with a foreign power, specifically Britain – largely the original target of the doctrine – America was overriding centuries of precedent …”

Britain wasn’t the original target of the doctrine at all, far from it. In fact, Britain was the nation that approached the US with the idea for such a doctrine in the first place, so as to prevent any of its european competitors getting in the way of free trade in the Americas.

Not only that, Britain was the sole nation that enforced the doctrine for the first handful of decades or so of it’s existence. The USA literally relied on the Royal Navy to enforce the Monroe Doctrine until the end of the 19th century.