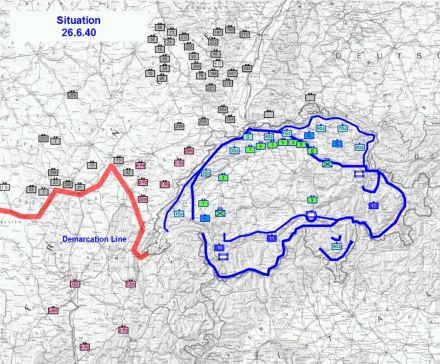

It is now November 9 1940. The bitterness of the Battle for Switzerland is something that will live with all Swiss and those German soldiers who participated. Out of the 800,000 Swiss under arms on September 24, 120,000 did not reach the redoubt. Only 15,486 of these soldiers were taken prisoner. In fact, there are more French and Polish prisoners in the German laagers then there are Swiss!

The Zytglogge in Bern, Switzerland.

Guisan and his staff are secure in the Redoubt, with the Germans unable to penetrate the massive defense works. However, the Germans are rather unwilling to commit so many forces to the strategically irrelevant alpine region. In the areas at higher altitude, the first snow has fallen, tabling any large offensives until the spring of 1941.

No less than 20 divisions are in occupied Switzerland, and tensions between occupier and occupied are running extremely high. Just as in Czechoslovakia, all popular gatherings have been banned. Weapons and wireless sets owned by private citizens have been ordered to be turned into authorities, including hunting rifles.[1] Heeresgruppe C has not been redeployed to the eastern front for a Russian offensive, and Wilhelm von Leeb has established his headquarters in occupied Bern for the winter.